There is a silence so loud it drowns generations.

It echoes not in words, but in what we are told to forget—our pride, our resistance, our divine origins.

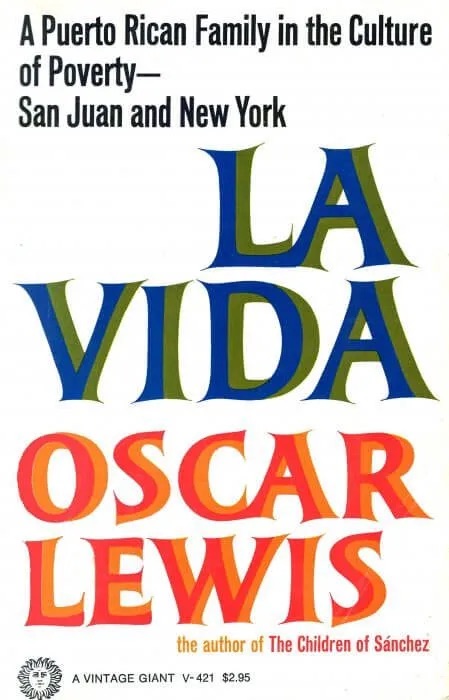

In the 1960s, a book called La Vida: A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty was paraded through academic circles and policymaking rooms as a model of sociological insight. But for those who see with ancestral memory, it was something else entirely: an early blueprint for entrainment.

This post continues the story begun in my earlier piece on the Puerto Rican medical experiments. There, I documented how the island’s population—especially carriers of the C1 haplogroup—was targeted for experimental research tied to Epstein-Barr Virus and immunological resistance. But what followed those experiments was just as calculated: the shaming, fragmentation, and dispersion of a people whose biology and spirit posed a quiet threat to empire.

It begins with a book.

It ends with a diaspora.

I was 13 the first time I picked up La Vida.

I found it tucked on a shelf among my mother’s books. Intrigued, I began reading—absorbing the vivid, often disturbing stories within.

Partway through, my mother’s niece noticed the book in my hands. She paused and asked, “Do you understand what you’re reading?” I nodded.

She replied, “That is not a good book. It is full of lies.”

And just like that, I stopped reading. But the impact had already taken root. It was my first encounter with the idea that non-fiction could be fiction—that “truth” in a book could be a fabrication.

That moment would shape me forever. It planted the seed of discernment that guides my life to this day.

1. The Shame Was the Spell

Books carry spells.

Not always the kind cast with candles or chants—but those woven through repetition, image, and silence. La Vida was such a book.

Subtitled A Puerto Rican Family in the Culture of Poverty—San Juan and New York, Oscar Lewis’s 1966 ethnography painted a portrait of Puerto Rican life that was intimate, graphic, and disturbing. It was praised in mainstream academic and policy circles as a masterwork of urban anthropology. But to anyone reading with eyes attuned to spiritual memory, it was also a weapon.

The weapon was shame.

Page after page of La Vida recounts stories of betrayal, addiction, incest, violence, spiritual abandonment, and dysfunction. The characters are not symbols of resilience, but of failure. Their struggles are not framed within the larger systems of colonial control or economic displacement—but as products of internal, generational moral decay.

There is no redemptive arc. No indigenous wisdom. No mention of Taíno ancestry. Just a cycle—a loop of pathology masquerading as reality. This is how entrainment works: it embeds a narrative so completely that it becomes the lens through which we view ourselves.

Even faith is depicted as shameful or confused. This is not just a portrait of poverty. It’s a ritual of humiliation.

And in its wide circulation—first among scholars, then policymakers, and ultimately the public—La Vida began shaping both internal identity and external perception. It created the conditions for Puerto Ricans to internalize inferiority and for outsiders to justify control.

The real danger of La Vida wasn’t that it told lies. It’s that it told partial truths without sacred context, then broadcast them as the whole.

And that’s how shame becomes policy.

That’s how memory is rewritten.

2. Oscar Lewis and the Ford Foundation’s Role

To understand La Vida, we must also understand the forces that enabled it.

Oscar Lewis, the anthropologist behind the book, rose to fame with his earlier work on Mexican poverty. His concept of the “culture of poverty” gained traction not only in academic spaces but also among policymakers seeking a framework to explain—and manage—urban underclasses.

Among his backers: the Ford Foundation.

Though direct documentation remains buried or obfuscated, multiple lines of inquiry suggest that Lewis’s work was supported—if not commissioned—by funding pipelines tied to the Foundation’s Special Studies Initiative. This initiative, operating in the Cold War shadow, acted as an intellectual front: a way to influence global populations by shaping how they saw themselves.

The Ford Foundation had a long history of supporting “development studies,” “population control,” and “cultural transformation” projects across the Global South—often aligned with U.S. strategic interests. Puerto Rico, though a U.S. territory, was treated similarly: a testbed for policies in housing, reproduction, education, and behavioral science.

Lewis’s ethnographies fit perfectly into this structure. They provided a narrative scaffolding for intervention:

- Not resistance, but pathology.

- Not sovereignty, but dependence.

- Not culture, but chaos.

If you reduce a people to dysfunction, you justify restructuring them.

And this is the deeper utility of La Vida: it fed the idea that Puerto Ricans were incapable of self-determination without outside control.

So while Lewis was positioned as an objective ethnographer, his work functioned more as soft propaganda. The goal was not merely to observe, but to condition.

3. Operation Bootstrap: Not Uplift, But Dispersion

The story we are told about Operation Bootstrap is one of progress.

In the 1940s and ’50s, Puerto Rico launched a sweeping economic reform program meant to transition the island from agriculture to industry. U.S. mainland corporations were invited in with tax incentives, factory jobs were promised, and mass migration to mainland destinations was cast as the path to prosperity.

But when we peel back the glossy narrative, a different picture emerges.

According to independent sources like @agent_mock, Operation Bootstrap was not merely economic development. It was a controlled dispersal. A strategy designed to fragment and water down the C1 haplogroup: the mitochondrial lineage carried by many Puerto Ricans, especially those with indigenous Taíno ancestry.

Why target this group?

Because the C1 haplogroup isn’t just biological. It’s spiritual. It is linked to high pathogen resistance, to ancestral memory, and to a deeply encoded resilience that persisted even through conquest. For those invested in control—whether military, medical, or psychological—such resistance posed a problem.

And so, Operation Bootstrap became a cover. On paper, it was about “jobs.” In reality, it was about movement:

- Away from sacred land (like El Yunque).

- Away from cultural cohesion.

- Away from spiritual inheritance.

Dispersal broke the code.

Isolation silenced the stories.

Poverty returned—this time in diaspora.

3.5 Two Narratives of Diaspora: Mainstream vs. Memory

In contrast, voices like @Grok—who rely strictly on mainstream sources—frame the diaspora as an unintended outcome. They describe the migration as a side effect of rapid industrialization: too few jobs, too many people, not enough support.

According to this version, Puerto Ricans left for survival. Not because they were driven out, but because they were pulled by opportunity.

But this view misses the design.

When only state-sanctioned data is considered “fact,” deeper motives disappear. The strategy of dispersal—if acknowledged at all—is reduced to a bureaucratic oversight. Yet every migration route, housing policy, and recruitment scheme fit into a larger pattern of engineered exile.

Both stories track the same migration.

Only one sees it as intentional.

4. The Loop They Created

To reinforce the need for dispersal and intervention, the narrative had to be consistent. The image of Puerto Ricans—especially those left behind on the island—had to remain one of chaos, dependency, and moral decay. This wasn’t a one-time portrayal. It was a loop.

A psychological conditioning loop.

Crime → Addiction → Poverty → Moral Collapse → Back to Crime.

A cycle, uninterrupted. A trap that looks self-made.

This loop does three critical things:

- Shames the population into silence

- Justifies outside control

- Erases memory of spiritual strength

In mainstream narratives, this cycle is described as the “culture of poverty.” But in truth, it was a culture of entrainment—crafted not by the people, but by those who studied them, judged them, and rewrote them.

Once embedded, the loop doesn’t require reinforcement. It plays itself. In schools. In media. In family shame. In spiritual silence.

It becomes the unseen drumbeat of the colony.

5. Masked and Injected: The Next Phase of Entrainment

Cultural entrainment is not confined to the past. It evolves.

The same tools that once shamed Puerto Ricans into compliance have expanded into the global theater. The loop of “deficiency” followed by intervention has become a planetary ritual.

We see it in the Medical Industrial Complex, which capitalizes on fear, shame, and dependency:

- You are biologically flawed.

- You are a risk to others.

- You must be corrected, contained, or controlled.

And so, when a virus came, we were already conditioned.

Millions accepted experimental gene therapies to avoid a cold. Millions masked their faces and taught their children to fear human breath. Compliance became virtue.

But this didn’t begin in 2020.

It began long before, in the quiet normalization of shame. In the idea that our bodies are problems, our communities broken, and our judgment untrustworthy.

For Puerto Ricans—especially C1 descendants—the pattern was already established:

- Experimental testing under the guise of medicine

- Mass migration under the guise of opportunity

- Medical obedience under the guise of safety

What they called “bad genes” were sacred codes.

6. What They Tried to Erase: The Spiritual Core

There is a reason shame was the weapon of choice.

Shame disconnects. It severs memory from meaning. It makes you question not only who you are—but whether you were ever worthy to begin with.

For the descendants of the Taíno, this shame was layered over centuries. But some things cannot be killed.

The C1 haplogroup is more than a set of mitochondrial markers. It is an encoded memory. A cellular reminder of what came before the conquest. It carries the strength of El Yunque, the songs of the forest, the sacred relationship to earth, spirit, and sky.

They tried to erase this by displacing the people.

They tried to overwrite it with poverty, pathology, and fear.

But the spiritual core remains.

We carry cemi in our bones.

“Each mind/body/spirit complex has a unique path. Use that uniqueness to find the way to the Creator.”

—The Law of One, Session 66.16

This is why we were targeted.

This is why they still fear us.

Because once we remember who we are, their control breaks.

Conclusion: The Spell is Broken

I am a U.S.-born Half-a-Rican.

My mother came from the island—Puerto Rico—where her family was raised, lived, worked, and suffered quietly beneath the shadow of experiments never acknowledged, and losses never explained.

I was born into the aftermath.

A third-generation descendant of the Puerto Rican experiments.

My body carries the memory, and my soul carries the fire to speak what was buried.

I never met my grandparents. I was told they were too sick. I never knew them, but I knew the grief.

I saw it written across the face of my mother—a face shaped by sorrow.

First the death of her parents, then the passing of each of her eight siblings, one by one, taken by diseases she believed were caused by poverty… or by “bad genes.”

That phrase followed me, too.

When I was diagnosed with fibromyalgia in 2008, I was told the same thing: “It’s your genes.”

As if suffering was my inheritance.

But today I know the truth is actually the opposite.

What they called “bad genes” were sacred codes—signs of resilience, not weakness.

Resistance mistaken for defect.

Spiritual sovereignty misdiagnosed as dysfunction.

But I do not write this in anger.

I write this in defense.

In defense of my mother, whose lineage was sacred before it was studied.

In defense of my aunts and uncles, who bore their pain without explanation.

In defense of the grandparents I never got to love.

In defense of the generations now rising, who deserve the truth.

They wanted us scattered, silenced, and ashamed.

But the line was never broken.

I am still here.

We are still here.

And we are remembering.

The spell is broken.

Make a one-time donation

Make a monthly donation

Make a yearly donation

Choose an amount

Or enter a custom amount

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

Your contribution is appreciated.

DonateDonate monthlyDonate yearlyDiscover more from Child of Hamelin

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.